For all their talent, Bud and Lou were not innovators. The routines they mastered had been honed to perfection years earlier, in Vaudeville. The Boys had come to know what worked for them and they felt no need to experiment. Critics of the time complained about Abbott and Costello serving up “the same old corn” in picture after picture, but the public didn’t seem to mind at all.

It’s almost impossible, today, to grasp the magnitude of Abbott & Costello’s popularity. They had a huge constituency of fans, having been on radio continuously for over a decade. They played personal appearance gigs to packed houses. They made two pictures a year, but with older titles constantly re-issued, you could have 6 or 7 Abbott & Costello comedies in circulation every year. The fans just couldn’t get enough of them. The Boys were box-office gold.

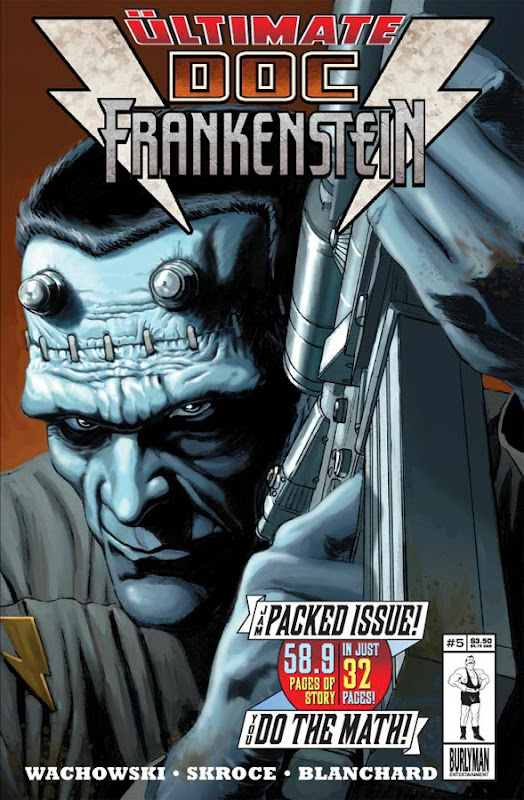

The Monster : Glenn Strange

Bud and Lou often complained, not without reason, of being saddled with uninspired supporting casts composed of clock-punching contract players. This time, they had no cause for worry.

Lon Chaney, Jr. reprised his signature role as the terminally anguished Larry Talbot. He’s a good guy, working with Bud and Lou to prevent Dracula from reviving the dangerous Frankenstein Monster, but he’s also a walking time bomb who can morph into The Wolfman and turn on the Boys at any moment. A nice surprise was seeing Bela Lugosi, in great form, don the Dracula cape again. The part had been essayed most recently by John Carradine, in top hat and fake mustache, while Lugosi had languished as a Poverty Row villain. Here, Lugosi was given a good, substantial role, and he handled himself with Continental aplomb, dignity intact, while the comics whirled around him. It was to be Bela’s last major film.

The cast of principals was rounded out with Jane Randolph as Lou’s sweetheart, Lenore Aubert as the evil and fatale Dr. Mornay, and the part of the Monster was assured, again, by Glenn Strange.

Strange had played the Monster in two previous outings but his screen time had been limited to being strapped on a slab until the final reel when, spurred by some mad scientist and his obligatory hunchbacked assistant, he rose, growled at the torch-carrying mob, and promptly walked into some quicksand, or a wall of fire. The End.

This time, the Monster was used throughout the picture, and he had the best, most fun scenes interacting with Bud and Lou.

Strange played the character as a stoic hulk, moving slowly and deliberately, hands out, like a blind automaton on remote control. His performance is rarely given the credit it deserves, but watch him closely in this film. This isn’t just a stuntman clomping around, it’s a real performance in pantomime. In a couple of scenes, incrementally sitting up at Dracula's command, or mechanically climbing the stairs in the gorgeous island dock set, Strange moves with such clockwork precision that it almost feels like the film has slowed down. His timing, always half a second late in reacting, is robot perfect.

Glenn Strange made a career as a character actor in Westerns. As The Monster, he was eclipsed by Karloff, Chaney and Lugosi who had all played the part in “serious” pictures. Strange was thought of as the fill-in Frankenstein, the one who got the part only after the part was discounted. But it was Glenn Strange who would give the Monster its pop culture profile. When the classic, flat-top makeup was applied to his wide, craggy face, it gave him a big, square, boxlike head, and this look became the Frankenstein trademark, better suited for toys and Halloween masks than Boris Karloff’s sensitive features.

Shooting on The Brain of Frankenstein began on February 5, 1948.

Cult Status

The Boys pulled their usual on-set antics, playing a marathon game of poker in their dressing room and refusing to come out for rehearsals. When they did made it to the stage, shooting would be regularly interrupted by the frenetic Bobby Barber, Lou's personal stooge, hired to create pandemonium and keep the company in good spirits. Universal crewmen reportedly loved working on Abbott and Costello pictures. Veteran director Charles Barton calmly steered the picture through all the chaos.

The only incident of note came when a stunt went wrong and Glenn Strange snapped his ankle. Lon Chaney, a good sport, offered to stand in as The Monster and that’s him throwing Lenore Aubert’s double through the window. Strange returned to the set a few days later, wearing a leg brace. Another incident, much happier, involved a scene where Lou backs into a chair and inadvertently sits in the Monster’s lap. His predicament dawns on him when he realizes that he has too many hands. Take after take, Glenn Strange, who was called upon to keep a straight, stone face, couldn’t help but break up. No amount of editing could salvage the scene and the two men had to be called back later on for retakes.

The film’s shooting title, The Brain of Frankenstein, sounded too much like a straight horror film. When it was released, in August ’48, it was called, simply, Abbott and Costello Meets Frankenstein. To Universal’s delight, preview audiences whooped as soon as the title appeared onscreen.

In retrospect, it was an early case of product branding. Comedians and monsters had mixed it up before, but these were not your humdrum haunted house ghosts or the escaped cheapsuit gorillas that had stalked everyone from the Ritz Brothers to the Bowery Boys. Abbott and Costello — household names to begin with — were tangling with Frankenstein! The Wolf Man! And Dracula! These were characters established over almost two decades worth of films. Their names had weight and significance.

The film was a runaway hit, the 3rd biggest box office attraction of 1948, and it gave Bud and Lou a whole new formula to exploit. Over the next few years, they would go on to “Meet” all the monsters they could scare up, from The Invisible Man to The Mummy.

Critics of the time were kind to the film, but it would take a few more years for it to be recognized as the comedy classic that it is. When horror films finally came under scholarly scrutiny, A&C Meet Frankenstein was generally regarded as an insult, the final ignominy for monsters whose potency had been slowly eroded through increasingly cheap sequels.

In an article for Sight and Sound (April-June 1952), Curtis Harrington — who had been a friend of James Whale — wrote that Abbott and Costello Meets Frankenstein was “the final death agony of James Whale’s originally marvelous creation”. Carlos Clarens, in his seminal Illustrated History of the Horror Film (1967), lumped the film along with the portmanteau House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula, stating that “unconscious parody finally gave way to deliberate spoof” and adding, “By then, Universal was flogging a dead horse”.

Boris Karloff was known to glower whenever the film was mentioned, though he had gamely accepted to pose for publicity pictures, standing in line to see the film in New York, and he had gone on to play in two pictures with the Boys, Abbott and Costello Meet The Killer, and Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Lon Chaney, Jr., who’d had a ball making the film, came to believe its pernicious influence had killed off the old monsters.

But, of course, the monsters not only survived, their reputations grew. Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein is an intelligent and vastly entertaining film. It was beautifully done. It has wonderful sets and a magnificent score by Frank Skinner. And it is still funny today. In the end, it was as generous, respectful and deeply-felt an homage to the classic Monsters as, say, Mel Brooks and Gene Wilder’s Young Frankenstein was.

Universal’s Frankenstein, Dracula and The Wolfman did not fade away, they went out with a bang in a fabulous film, a true and glorious Last Hurrah. More importantly, Abbott and Costello Meets Frankenstein, with its reverent use of Universal’s classic monsters, forever cemented their reputation as dominant icons of popular culture.

References:

Abbott and Costello Meets Frankenstein on DVD.

Abbott and Costello in Hollywood, by Bob Furmanek and Ron Palumbo (Perigee Books, 1991). Out of print. You can still find a copy through Amazon Sellers or AbeBooks.

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein: Universal Filmscripts Series, by Philip J. Riley (Magicimage Books, 1990).